The Making of

THE GHOSTS IN OUR MACHINE

By Liz Marshall

The Ghosts In Our Machine was nominated for a whopping 4 Canadian Screen Awards. This blog focuses on just some of the creative and editorial decisions that went into the film. Of the 60+ screenings I attended around the world between 2013 – 2014, audiences consistently expressed (and continue to express) appreciation for the film’s gentle dramatic effect, character-driven approach, its cinematography, photography, music, sound design, and more.

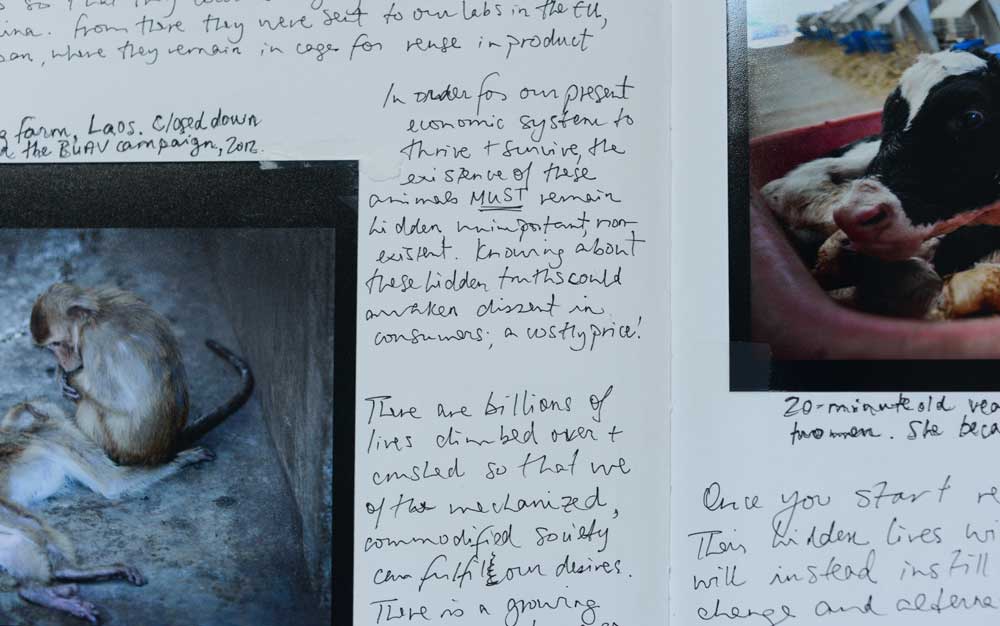

The themes and questions explored in The Ghosts In Our Machine incubated for many years.

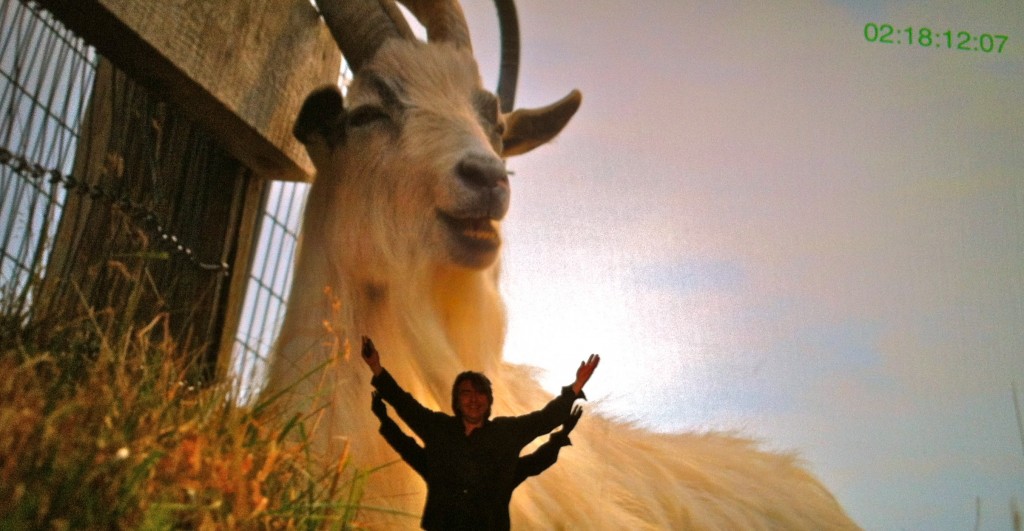

I grappled and marvelled and searched for a compelling angle. In 2006, as I was getting to know Jo-Anne McArthur (Jo) and her photographic work We Animals, cinematic ideas began to stir. Jo’s images invite us to see all animals as individuals. Her intimate photos transport us to the front-lines where we lock eyes with helpless creatures trapped within the machinery of our consumer-driven world.

In 2010, off the heels of my previous film Water On The Table, I was ready to formally commit to the development of The Ghosts In Our Machine and saturated myself with reading materials and animal rights films. I realized I needed a sympathetic and relatable human subject to anchor the issues. I asked Jo if she would consider being featured in the film, and explained that her presence would be a powerful narrative device to help us creatively access the lives, emotions and predicaments of the animals. She immediately understood, and agreed.

More than any other filmmaking journey, I committed myself to a long personal process of reflection; to peel back my own blinders and to face some deeply held prejudices. As a social-issue filmmaker, and an animal lover, I realized I had much to learn about the moral significance of non-human animals, and this precise discovery helped to shape the direction I wanted for the film.

The film needed to reach a wide audience without compromising truth or integrity. The film needed to gently remove people’s blinders to reveal the ghosts; the billions of individual animals hidden from our view, and to inspire deep and lasting reflection, for a diverse global audience.

How could The Ghosts In Our Machine elevate this marginalized social justice issue? This occupied me, always.

I carefully selected an accomplished team of cinematographers, editors, composer, sound recordist, sound editor, and sound mixer to help achieve the seemingly impossible goals of the film. An open heart and mind, passion and perseverance was essential.

In conversation with some of the film’s creative team, this blog lifts the veil to reveal techniques and reflections. Hope you enjoy.

PHOTOGRAPHY & CINEMATOGRAPHY

LIZ: Jo’s photographs provided the main pillars:

eye-level; close proximity; naturalism; equality.

Normally I work with one cinematographer on a film, but for this film I wanted to blend some different influences with the intention of creating one cohesive voice. The subject matter is so intensely personal for everyone, I was interested in the creative journey, for all of us.

Jo, I wanted the film to be a seamless visual world between your photos and the moving images. The editors applied so much skill and effort to find the right rhythm and balance. Do you think the film achieves this? Do you wish we had utilized more of your photos in the film? Or, some different ones? If so, which ones come to mind?

JO: You really did labour over this! And you really achieved what you set out to do. To illustrate this: I asked many people how many photographs they thought were incorporated into the film. They all guessed WAY UNDER the actual amount. That’s because the weaving of stills into the moving pictures was seamless, and this seamlessness is a compliment I often hear about the film. I don’t wish other or more images were used. If I were unhappy with the film then perhaps I’d have a different answer! The only image I would have worked with differently was the poster! I still suspect that the poster was a bit too dark/foreboding. There’s a lot of hope and light in the film, and showing that might have made the film more inviting at first glance. I had to make the same decision w/ the We Animals book.

LIZ: John Price is a magician. I’ve had the pleasure of working with him since 2008. Expressing interior space of the protagonist is what I strive for, and John helps to achieve this brilliantly. I like (love) the interplay of light and dark and John is unafraid of the dark, he shapes it masterfully to illuminate the light. John was the main cinematographer for the film. I wanted his continuity while filming with Jo, which included our big trips to Farm Sanctuary, to New York City, and to Europe for the undercover fur investigation, and the zoo and marine theme park. Two other brilliant cinematographers contributed to the film, Iris Ng and Nick de Pencier. And, I shot approximately 20% of the film, mostly as the B-camera, with John in the field.

JOHN: I like shooting actuality with people that are socially, politically and artistically engaged. I mean, I love it. I think the transformational qualities of the cinema are so frequently ignored, wasted or overlooked and to work on projects that have both an artistic and humanist compass are a gift. It’s easy to commit to something that I can relate to and that is such an important discussion for us at this point. It’s also important that it’s not propaganda… less journalistic and sensationalist. That it creates an opening for the audience to locate themselves and find some kind of connection with the subject… empathize. That’s my preference as a viewer really and it’s naturally instinctive to try and record moments this way. It’s just very very lucky and rare when you are afforded the opportunity to participate in this kind of project.

LIZ: In finding and refining the visual language of the film in various locations over the course of the production year, what was your strongest instinct?

JOHN: In general the idea of naturalism was a strong guide from a conceptual and practical point of view. I find that working with and shaping available light – and in particular natural sources of daylight – humanizes the subject somehow. I think the ‘artifice’ in artificial lighting effects the way an audience interprets things subconsciously. When you start throwing in backlight, rim light, kick light for interviews it can’t help but to take things into the realm of theatre and ‘acting’. Of course there are ways to achieve naturalism with artificial lighting but generally this approach requires larger light sources further away from the subject that are diffused or bounced through various material / textile. This is impractical when you are travelling with a very small crew and budget is a factor.

You and I had discussions at the beginning about trying as much as possible to humanize the animals and what that meant visually. Being with them at eye level was a starting point. Being physically close to Jo and the animals was also important. Fortunately Jo was easy with that presence from the beginning no doubt because she completely trusted you and believed in the project. I think that once the subject gets used to the presence of the camera that it (the camera) becomes more invisible and so what happens in front of the lens becomes less performative and more natural. It does not hold true in every case but if the subject is open and honest it’s transparent and creates the space for empathy, which is so important for documentaries like this.

I was moved most intensely trying to record the experience of the ‘non-human’ animals held captive. I don’t know if there is anything more tragic than looking into the eyes of a primate behind bars who has committed no crime and has so little space, privacy, or hope. You know there is so much going on inside and the energy of unhappiness seems so plain and so raw. The fur farms were another site of unthinkable suffering. The repetitive obsessive behavior, the screaming, and the filth… it’s just so dark. How we as a culture have arrived at this moment where what used to be needs have become wants… and how deeply destructive (and ultimately unnecessary) their production and distribution have become. The only counterweight to this darkness is to engage with other individuals who are asking these fundamental questions and looking for clarity. That and bringing up my kids so they are aware of these things so they can make better choices and with any luck be part of a positive change.

LIZ: Iris Ng – can you tell us what it was like for you to focus almost exclusively on capturing the details and emotions of Maggie and Abbey? What were the challenges and joys, both technically and creatively?

IRIS: Following the movements and emotions of non-human subjects called upon me to somewhat temper my doc shooting instincts. Liz, you emphasized in our early conversations, the importance of focusing on Maggie (and eventually Abbey’s) world by physically getting down to their level to honour their perspective. This meant holding composition on them and allowing the human characters to fall outside of the frame, cropping their bodies and faces which felt unnatural at first.

It was also challenging technically, to stay at the height of Maggie and Abbey’s eye-level as they moved sometimes frantically and excitedly throughout their world. But it was also joyful to follow their impulses and observe their reactions to each other and to objects and people around them. Generally, we had to let go of expectations and accept a higher degree of unpredictability of how a given scene would play out. In retrospect, it required a kind of heightened version of how I aspire to approach the variety of subjects in my other work, and this experience has taught me a great deal.

I’m very honoured to be part of this cinematography team by the way, it created a unique and unexpected balance between the film’s aesthetic and powerful message.

LIZ: Nick de Pencier, I wanted you as a cinematographer on this film because of your extensive experience shooting with 2k and 4k formats, and because you have filmed so much with wild animals. Can you share some of your acquired knowledge about filming with animals?

NICK: Working on the images in Ghosts, and in the discussions we had leading up to filming, I found myself thinking a lot about time. Of course all films are time capsules where the filmmaker collects disparate moments and puts them together for a viewer to experience later in their own time, but I find that filming animals brings an entirely unique time-dynamic to the production process. When I first started filming nature documentaries I had to completely re-calibrate my expectations and approach because the rhythms of filming people and cities just do not apply when you’re trying to synchronise with the natural world. In our constructed societies, it’s possible to force things to happen and manufacture moments through a variety of means. None of this manipulation works in the natural world. I learned that if I brought any frenetic, urban mindset to filming animals, not only would I have very little success in being reactive and sensitive to the animals I was trying to film, but the authenticity of the moment would be lost. There was a divide that I was not bridging: I would be moving too much, or in the wrong way, my presence would cause disruption or fear, and of course the results and the experience were frustrating. Over time I worked to change my approach, and to try and integrate myself with my surroundings. This of course yielded much better results, but was also an incredibly welcome change in perspective and in just simply being. Feeling that evolutionary connection with the animals and a non-constructed environment profoundly re-affirms my belief that this is the healthiest mode of existence for humans and all beings. It was such a pleasure to have been able to achieve this state while we were filming together, and to recognise that it was shared amongst all the collaborators.

LIZ: I wanted to bookend the film with an essay-style contemplation for audiences. Extreme close-ups and slow motion footage of animals invite viewers into the visceral sensory worlds of horses, cows, sheep, cats, dogs, pigs, primates, a guinea pig and a dolphin. You composed these images on your Epic RED camera at ultra high speed (slow motion) at 4K resolution. Audiences marvel at the intensity of these images. The opening and closing sequences of the film are accompanied by a minimalist soundscape, including the disembodied drifting voices of scientists, lawyers, professors and activists, who ruminate on the animal issue. What is the power and significance of slow motion in film?

NICK: Another part of the time equation perceived working on Ghosts was that we talked a lot about filming the animals in slow-motion. For me, cinematic tricks used gratuitously always deflate the power of a film, but you were convinced – and you were right – that certain images of animals in slow motion would be a powerful addition to what you were trying to accomplish in Ghosts. If one of the goals of the project was to get people to think about animals differently, I think making time elastic and slowing down certain key moments with the animals was a great choice. I think as viewers, it let us consider them in a more contemplative way – a more existentially charged instant where because, being slowed down, they are out of their time continuum, they pop out of time for us too and so we can examine them more minutely, while being more aware of ourselves in that moment. This is a rare and precious thing in film, and a real accomplishment.

SOUND RECORDING

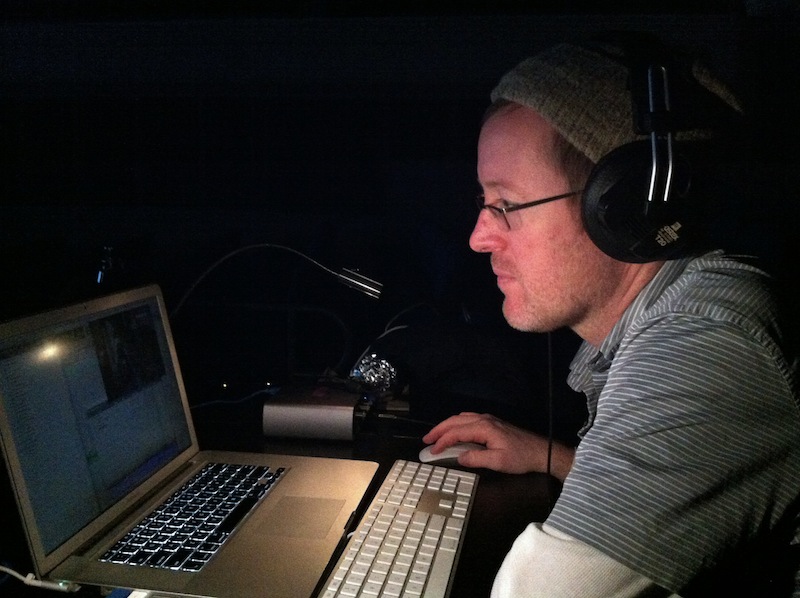

LIZ: Jason Milligan – as a documentary location sound recordist, you have traveled far and wide and worked on many different kinds of productions (including films with me since 2006). Gathering the sounds of the animals up-close during the fur investigation and at Farm Sanctuary was especially important for the film. What were the challenges and highlights?

JASON: I love animals so working on a film that showcased the plight of non-domestic animals was very important to me. The fur investigation was difficult. The sounds of the animals were quite depressing. Locked up and mistreated they could barely manage a yelp. You hope working on a project like this that after watching the film, people will understand that fur coats and fur trim are extremely unethical and choose to purchase something with a synthetic alternative instead. Farm sanctuary is an incredible place staffed by incredible people. I loved it so much there that I returned with my wife for our honeymoon. It was great seeing all the animals living freely and at peace. The sound highlight for me was capturing the snoring of Teresea the pig as she slept under the blanket on a freezing day at Farm Sanctuary! Clearly she was relaxed and calm and free from the abuse and confinement it once knew on a factory farm.

NARRATION VS. INTERIOR DIALOGUE

LIZ: Jo, rather than having formal narration or filming sit-down interviews with you, I wanted more of an interior diary/journal voice that would help inform the film’s tone and structure. We recorded several in-depth and very personal conversations/interviews with you in a small cozy recording studio, periodically, spanning early 2011 to late 2012. What was this process like for you? Was it helpful, effective, awkward, ineffective?

JO: Yes, it was very personal but I trusted that you would use personal information in a way that helped and complimented the message of the film. As much as you made studio recordings feel safe and comfortable, I at times struggled with self-consciousness. It took some work to “get over myself” and take confidence in knowing that what would make it to the film would serve a specific purpose and that ultimately, it was not about me, but about animals, and helping animals, and the journey of something trying to do that. The studio recordings we did were used sparsely and that narration definitely loaned itself beautifully to the film.

PICTURE EDITING

LIZ: Roland Schlimme – when I contacted you in 2011, what was it about this project that convinced you to commit yourself as editor? And, throughout the epic process of editing the film’s Assembly, what did you discover?

ROLAND: It’s a real privilege and pleasure to talk to filmmakers about their projects – even ones that I don’t end up editing. In terms of deciding what to take on, there are always many factors – both interesting and mundane.

With Ghosts, subject matter was maybe more of a consideration than usual – I was interested in and largely ignorant about questions around animal rights. So it was an opportunity for me to broaden my awareness around a subject (as many of the films that I work on are). But subject matter is only one aspect to consider – as we hadn’t worked together before, it was a question of feeling out that collaboration in our first meetings: whether there was some rapport creatively and otherwise. I don’t really know how those decisions get made, but on some level it’s a question of faith in the project and faith in the relationship. I think I was struck by your commitment, focus and openness in approach. And you already had great collaborators on board, shooting with you.

There are also simple practical considerations – and on this project I was already committed to start Watermark in the fall of 2012; so it was great that we could work out a schedule where I worked on the assembly with you (before Rod came on) and I could go on to my commitment with Jennifer Baichwal. I think it helped that Rod and I had worked together before.

In terms of our work together and the assembly, it’s hard to sum it up; the discoveries are often pretty specific to the material and scenes. On the question of animal rights, I was doing my own research on a more philosophical level – reading perspectives on the question. But it was clear that the film wasn’t philosophical on the question. The strength of the film was more subjective – being able to see the world through Jo-Anne’s eyes and work. One common question on issue-oriented films is how it’s possible to effect change – what is it that might change someone’s thinking or beliefs? Empathy is a powerful tool in that respect. It was clear from the outset that we had to find the strongest moments in her experience (in your experience together, filming) that could crystallize that in some way.

Ultimately, I think that’s the strength of the film – illuminating an issue through Jo-Anne’s specific perspective.

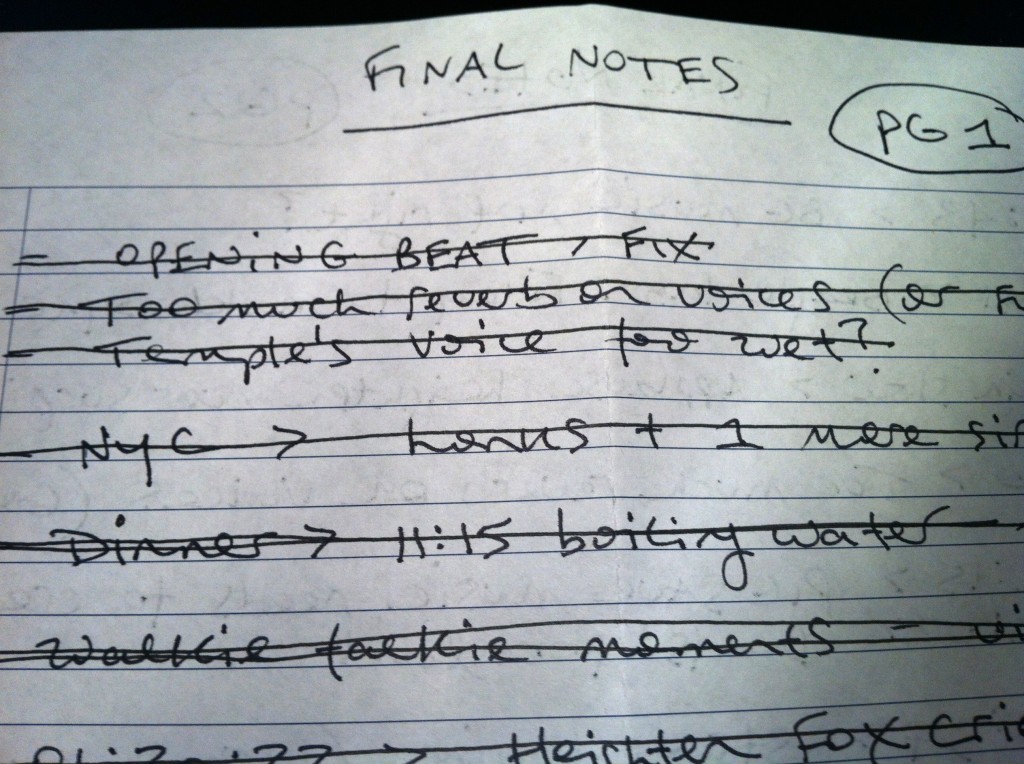

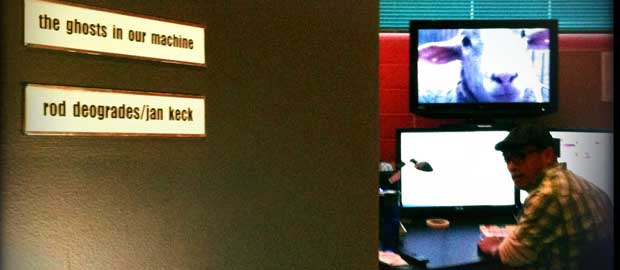

LIZ: Roderick Deogrades – What was it like for you, both technically and creatively, coming into this project 4-months into post-production?

ROD: Starting the project after all the work that you and Roland had put in was certainly daunting and overwhelming. As an editor, I am used to being familiar with all the footage going in. Shifting from my usual approach took a little bit of time. But soon enough, owing much to how Roland organized the footage along with your extensive familiarity with where all the pieces were, I got past the slight disadvantage of not seeing everything and was able to effectively do my work as an editor. Despite the fact that it was in assembly stage, it was also very liberating going into a film that already had a direction structurally. Much of what Roland did was so great. And using that as a jumping point for inspiration to try different approaches was a lot of fun. Knowing that if anything we tried didn’t work, we always had the original cut to draw from. This I feel, allowed for more experimentation, especially when trying to shape the film’s final structure.

This is the second film that Roland and I had handed off to each other. The previous instance, it was Roland that took over after my assembly. And it once again proves that two heads are better than one (well… three really. Two editor’s work would mean nothing without the director beside them).

LIZ: Rod, we then worked closely from October to December to shape and refine and lock the film. What was your strongest instinct during this intensive process? And, what was your greatest take away in helping to create a film that is changing the world for animals?

ROD: When I edit a scripted film, I always try to make sure that the audience can connect with the characters in the film. The actors’ performances play a huge role in accomplishing this. Without it, there’s a disconnect between the viewer and the people on screen, resulting in a less successful film. When editing documentaries, I’ve always applied the same approach with the doc’s main characters. In TGIOM, these are the animals. So treating them as any character I would normally edit was a real pleasure – to help highlight their personalities, emotions, etc. and show them as living and feeling beings is part of the reason, I feel, TGIOM works so well. It was a crucial tool to show audiences that animals were sentient beings, deserving of rights. My strongest instinct was to always be aware of this throughout.

My greatest takeaway is the amount of pride I have in being involved in such an important cause. It has changed me in the ways I approach living on this planet and sharing it with our animal friends. It has been a couple of years since we finished the film, yet the lessons still resonate. I only hope that my contributions have done the same to everyone who has seen the film.

MUSIC SCORE

LIZ: Bob Wiseman – our creative process was unique because you didn’t mind us (me and Rod) playing around with the music stems you created. Sometimes I wanted a very stripped down and understated ambience. Your versatile unconventional sensibility provided many options for us. Can you tell us about your process?

BOB: As a composer I see myself as responsible to help the director get whatever their vision is so if I make music and it has separate tracks it’s totally fair for the director or editor to fuck around in any way they wish. My job is to try and do that without complaining.

POST PRODUCTION SOUND EDITING

LIZ: Garrett Kerr – the most fundamental aim of the film is to give cinematic agency to the animals through sound and picture, and to push the envelop past the point of discomfort, if need be, to make the point that animals are conscious living beings. What I love about working with you Garrett is that you approach sound in a deeply philosophical way. What was it about Ghosts that inspired you? And, can you reveal a conceptual signature that you applied to the film’s overall sound design?

GARRETT: I have to preface this response by saying that I’ve never worked on a film that presented the kind of challenge that Ghosts did. As a sound designer, it’s not uncommon to search for interesting ways to tell a story through the soundscape, of course. When done at its best, this is usually executed in ways that are subtle and which engage the audience in a subconscious way. Generally speaking, I usually try to err on the side of a subtlety in which these design elements may be lost on the audience rather than risk becoming obvious or apparent thus distracting the audience and pulling them out of the film. Ghosts presented many opportunities to do this, but, as a team, we found ourselves struggling with the dilemma of how to engage these. I’ve never worked on a film where the “voice” of the subject was so important. In discussing the approach to the sound of the film with Liz, there was a clear understanding of the need to help supply the voice to these living creatures who are not necessarily voiceless, but who lack a means of communicating effectively to those that currently hold dominion over them — ineffective not due only to proximity, but even those close enough to hear their screams are rarely moved to try to help them … In searching for sounds to fill in the landscape and project the calls for help from the animals on screen, we focused on two things:

First, we tried to find authentic and legitimate sounds for the animals being shown, but that spoke to us most effectively. Admittedly, it was unpleasant to comb through recording after recording of animals in various degrees of distress, anguish and terror, searching for sounds that would have the greatest impact (I know that was just a mere shadow of what it is surely like for Liz and Jo-Anne to walk into the midst of the abuse searching for the most effective images and storylines to connect with the audience). When we found the most powerful sounds that we could, we would build the landscape and then play it for Liz to get her take on its authenticity and honesty. For us, that was the balance — trying to make the soundscape as uncomfortable and resonating as possible, without crossing the line of truth. In the end, I suppose that only ones who would truly know if we’ve done justice in our work is the animals themselves, but, on some level, if the soundscape provoked anyone to sense the injustice, to feel a wave of compassion and a desire that the situation to be corrected, then something good has happened.

The second way we tried to entreat to the audience has less to do with the animals’ voices and more with the environment around them. We tried to draw attention to either the disconnect between the animals’ actual environment and their natural environment (by placing an abundance of technology such as cell phones and intercoms in the zoo scenes, etc.) or by embedding the sounds of the animals themselves in the mechanisms of our human environment (the ghosts in the machines!). Listen for the cat screech in the espresso machine, the dog yelps in the milking machines, the pig squeals in the transport trucks, the chimpanzee scream in the subway car etc. These sounds are subtle, and hopefully not noticed as one watches the film, but our hope was that they would embed a sense of … what’s the word? I want to say ‘humanity’ but that’s not it, of course — we need a word like humanity which addresses all living beings. Life! Sentience! Whatever that thing is, we wanted to embed that in the environment, to help us to remember that sentient, feeling creatures are living and dying in the fabric of the machinery that makes our human lives as luxurious and privileged as they are. The sounds of the ghosts that are in our machines.

POST PRODUCTION SOUND MIX

LIZ: Daniel Pellerin AKA: Mix Master, I adore working together. I refer to the mix process as the ‘jewel of the crown’. It’s the final phase of a very long and exhausting journey. Being in the mixing theatre with you is like being at the top of the mountain. The air is clean, and the view is expansive. You mix huge budget films over months, and low budget indie films and documentaries over weeks or days. With a nuanced film like Ghosts, we had just a couple of precious weeks in the mixing theatre, with 80+ layers of sound to make sense of, what was your guiding principal and wisdom? And, what is your acquired wisdom as a result of mixing a film that has such a positive impact in the world for animals?

DANIEL: As with the “larger” projects we are often involved with in designing and mixing sound for, “The Ghosts in Our Machine” is no less complex and no easier to execute than any of these. Simple narrative projects and even intricate visual stories are no less complex in finding a language that is compatible. The challenge with doing sound that does justice to Liz’s motion pictures is formidable. As with all that Liz Marshall directs and produces that we have collaborated with her on, the picture editing and music / sound editing / mixing has offered us many opportunities to create a sound design and mix style that will be supportive of her initial concepts and in full accord with her vision. That being said, it is not as simple as it seems. And in my estimation, the material and the concept of this project were conducive to a very bold and immersive style in conjunction with an engaging contemplative approach in the quieter passages, which requires a richer aural tapestry than most documentaries and actually most features for that matter.

What made this sound treatment engaging and effective in every respect, in my extensive experience, is an exciting blend of both the contemplative abstract musical and sound passages combined with a very bold visual style that brings you to experience internal moments from the animal’s perspective, in a most meaningful way. Quite a formidable approach, and as with everything we work on together, very effective to bring the audience to experience the subject matter in a more cinematic fashion. It creates a rich tapestry of sound and meaning that meshes perfectly with the strong and sturdy yet haunting and lyrical visual style that she embraces, expressing her concepts clearly and with purpose. Working with her and all our collaborators that have had the good fortune to work on her projects has been an extremely rewarding and fulfilling experience. It has in significant ways changed our lives forever and the way we perceive the natural world around us.

LIZ: Jo, being filmed in various locations over 1.5 years, to seeing pieces of the editorial process along the way, to then experiencing the full film at a private screening in a beautiful theatre with the Ghosts team and with your dad present – what was it like for you to see it all come together with yourself and your work elevated on the big screen? Can you recall the thoughts and emotions then (early 2013), compared to now?

JO: Then and now I just feel damn grateful that the We Animals work could be used and shared in such a hugely impactful way. I trusted you Liz from the beginning to present all of the work beautifully and honourably. I cried in the theatre at that first viewing – a lot! Seeing the culmination of years of work, put together so beautifully on a big screen is a rare experience; truly a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. The whole experience of being a part of the film was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. A rich learning experience, with the added bonus of forming bonds with you, the director, and the crew while working on such heart-wrenching and uplifting subject matter. Lucky me! I’m grateful for the experience on both a personal and professional level.

(Published 01.23.15. Updated 05.20.15)

###

View film credits

Watch The Ghosts In Our Machine anywhere in the world.

Director and producer Liz Marshall is an award-winning Canadian documentary filmmaker.

Comments are closed.